I have acquired this extraordinary “magical” painting for my office. It was done by Alexander Boguslawski –a professor of Russian Literature and Aesthetics at Rollins College.

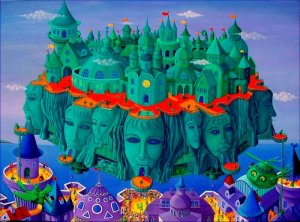

The Truth Is Out There was inspired by stories of UFOs, but these stories were, of course, filtered through the artist’s imagination. Since in most of the artist’s works we see fantasy worlds, this painting actually shows a meeting between the earthlings and the extraterrestrials, each inhabiting a world of their own. The extraterrestrial spaceship is a city built of a green material, and its foundations rest on sculpted female and male heads. The ship’s body conceals the rest of the city, but it is obvious that much must be going on within (the viewers need to imagine what exactly is going on). Some things are clear, however. The extraterrestrials are lovers of books; they emerge from the domed library and descend through the opening in one of the heads to the landing pad, from where, as we can see, they climb down to earth and bring the offering of books to the gathered crowd. The extraterrestrials seem to be of two kinds — the tall ones (apparently the leaders and the brains) and the short ones, the workers — mutations of Mickey Mouse and watermelons. They are surrounded by many extraordinary creatures, among which are huge birds they use as means of personal transportation, while their motorized “beanie-prop-hoppers” are capable of transporting at least several crew members. The earthlings are a colorful lot, as evidenced by their costumes, and they seem to prefer the purple building material. Of course, the careful observer will notice immediately that there is not much difference between the architectural designs of the earthlings and the extraterrestrials; it is actually possible that the latter visited earth long ago and were inspired by the physical appearance of the earthlings and by their architecture. It is clear that the earthlings are curious about the visitors and they are greeting them by offering them the keys to their city. Perhaps this painting provides the artist’s response to the recent slew of movies presenting the visitors from space as evil beings bent on destroying the human race. Or, what is also possible, the artist is communicating his desire that the earthlings read more books!